This is the story of Louisa, born in the Shenandoah Valley, about 1808-1810 to a woman named Dinah who was enslaved in the home of John McCluer (1750-1822) in Glasgow, Rockbridge County, Virginia. Dinah’s other children were named Richard, Samuel, Mary, Peter and Daniel, with her youngest daughter named Carolina. On the 10th of December 1821 a young Louisa would be inherited by McCluer’s daughter Nancy (1791-1833), who in 1820 had married James H. Alexander (1789-1835), whose enslaved property included a handsome young man named Archer Alexander (1806-1880).The young couple, Louisa and Archer married in the custom of those enslaved, in a ceremony referred to as “jumping the broom” as marriage was prohibited by law. In August of 1829, Samuel, Mary, Louisa and Archer were among twenty-one enslaved people taken to Missouri by the Alexander and McCluer families. By that time Louisa and Archer had begun their family, and on that journey, Louisa, was nursing not only her own son, but was also the “wet” nurse for a newborn of James and Nancy Alexander. For some reason, after the death of James and Nancy’s newborn, Archer and Louisa were forced to leave behind their son, Wesley, at a family member’s farm on the road between Lexington and Louisville, according to the family’s oral history. The caravan of four families reached Dardenne prairie in St. Charles County, Missouri soon after.[i]

In the early 1830s, a cholera epidemic was raging across the Missouri countryside, and Archer and Louisa’s enslavers would both die from the disease. In 1835, James H. Alexander’s will left instructions that none of his real estate or slaves were to be sold, but only leased, with all of the funds used to support the four orphans being raised by relatives back in Virginia. For the next ten years, the enslaved were leased out to various enslavers by the estate’s executor, an attorney named William Campbell (1805-1849) who also lived in St. Charles. For several years, Louisa would be leased to the local postmaster, and mercantile owner, James Naylor, whose family were prominent Presbyterians, and had established the Dardenne Presbyterian Church in 1819. During that time, Louisa’s husband Archer would work as a stone mason, brick mason and carpenter, building several homes in St. Charles County.

By the mid-1840s when the four orphans grew up, they inherited the property, including the enslaved. The enslaved were appraised, including Louisa and her seven children still living with her at that time. Listed in the probate, her children were: Eliza valued at $325, Mary Ann with a value of $300, a son who was also named Archer who was valued at $225, a son named James with a value of $200, a son named Alexander with a value of $175, a daughter named Lucinda, valued at $150 and a son named John, appraised at $125. By 1845, the family was torn apart as Louisa was sold to James Naylor, while her husband Archer became the property of the Pitman family, who lived about six miles away.

According to the 1860 Federal census, there were 114,931 slaves and only 3572 free Blacks in Missouri. St. Charles County had been first settled by the French in 1769, with the friends and family of trailblazer Daniel Boone settling there in 1799 and bringing along their enslaved. By 1821, the county’s city of Saint Charles became the site of Missouri’s first State Capitol. At that time, most of the residents were former residents of Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee who had brought their enslaved with them. But the decades of the 1830s, 40s, and 50s, saw a huge influx of German immigrants. By the beginning of the Civil War, the huge German population would choose to join the Union Army thereby preventing the state from seceding and create a state full of division in the loyalties of its’ residents. The conflict of the Civil War would have a huge effect on the life of Louisa.

In the beginning of 1863, Archer Alexander overheard a meeting of the area’s secessionist men in the back of James Naylor’s store. After learning that they had arms and ammunition stored in the icehouse on Captain Campbell’s farm, he took it upon himself to inform the Union troops guarding the nearby Peruque Creek bridge. It would not be long before it was discovered who the informant was, and he was forced to flee via the network known as the Underground Railroad, making his way to St. Louis, and leaving Louisa behind. Archer would spend several months separated from Louisa, but when he was awarded his freedom on September 24, 1863, he wanted to bring Louisa to St.Louis. Archer’s freedom was due to his benefactor William G. Eliot, the disloyalty of his enslaver Richard H. Pitman, and Archer’s important services to the U.S. military forces. Archer explained to Eliot “You see, sir, we’ve been married most thirty years, and we’se had ten chilluns, and we want to get togedder mighty bad. He said that three of the children, one of them a married woman, had already managed to get to St. Louis…” When Archer writes Louisa, telling her to ask Naylor how much it would cost to buy her freedom, she writes back:

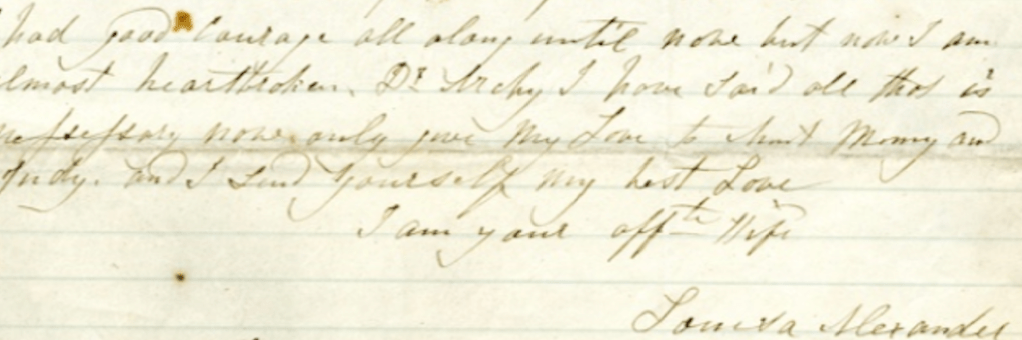

“Naylors Nov 16. 1863, My dr. [dear] Husband I recd. yr. [received your] letter yesterday and lost no time in asking Jim if he would sell me and what he could take for me he flew and me and said I would never get free only at the point of the Bayonet. and there is no use in my ever speaking to him any more about it I don’t see how I can ever get away except you send soldiers to take me from the house as he is watching me night and day Lucinda lives4 miles beyond this side of Troy. I have her little boy Jimmy with me. I heard from M. Anne about 2 weeks ago she is Washington both well and doing well she has all her Children with her but the oldest one and he is expecting to go to her every day If I can get away I will but the people here are all afraid to take me away he is always abusing Lincoln and Calls him an old Rascall he is the greatest rebel under heaven it is a sin to have him loose he says if he had hold of Lincoln he would chop him up into Mincemeat I had good courage all along until now but now I am almost heartbroken. Dr. [Dear] Archy I have said all that is necessary now only give my Love to Aunt Mimy and Judy, and I send yourself my best Love, I am your afft.[affectionate] Wife Louisa Alexander Answer this letter as soon as possible Sam told me that you were Doctor Buckners last Saturday night. they are always telling some lies about you.”[ii]

Louisa

Archer Alexander arranged for a longtime friend, a German neighbor, to bring Louisa and their youngest daughter to St. Louis for $20. Eliot shares the following story in his book Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom:

The German farmer had kept his word. He had told Louisa that on Saturday evening, soon after sunset, he should be driving his wagon along the lane near her cabin, and that if they could manage to get down there, he would pick them up, and put them on the road. So at dusk they strolled down that way separately, without bonnets or shawls, so as not to attract notice. Nellie was thirteen years old, a smart girl, and well understood the plan. Meeting at a place agreed upon, they only had to wait two or three minutes before their deliverer came. He was driving an ox-team, his wagon being loaded with corn shucks and stalks loosely piled. Under these, arranged for the purpose, he made them crawl, and covered them up with skillful carelessness, so that they had breathing-place, but were completely concealed. He then drove on very leisurely, walking by the oxen, with good moonlight to show the way. When they had gone about a mile, one of their master’s family, on horseback, overtook them, and asked the farmer if he had seen “two niggers, a woman and a gal,” anywhere on the road. He stopped his team a minute, so as “to talk polite,” and said, “Yes, I saw them at the crossing, as I came along, standing, and looking scared-like, as if they were waiting for somebody; but I have not seen them since.” Literal truth is sometimes the most ingenious falsehood. The man looked up and down the road, turned quickly, and went back to see if he could find the trace in another direction. The farmer, chuckling to himself, drove on as fast as his oxen could travel, and before daylight was at the place where he had promised to bring his human freight. Archer paid him twenty dollars for his night’s work.[iii]

William G. Eliot

Louisa and Archer were reunited, and able to make a home in St. Louis. Scared and nervous, they kept out of sight. Pitman had been arrested and jailed for his treasonous actions, and had his property confiscated as Martial Law dictated. Unfortunately, the couple’s reunion was brief. Eliot tells the story of Louisa returning to the farm of James Naylor after the wars end and taking sick and dying two days later. However recent research reveals that Louisa died in St. Louis and was buried at the City Cemetery. The history of that cemetery is fraught with removals, and unmarked graves. No longer are we able to locate those burials and the grave of Louisa is yet still unknown. The beauty and strength, tenacity and courage of Louisa, is marked with pride by all the descendants of Archer Alexander. She was the great-great-great grandmother of Muhammad Ali, born Cassius Clay in Louisville, Kentucky, through her son Wesley, the baby left behind.

[i] For more about this journey see From Virginia to Missouri https://archeralexander.blog/2020/08/20/20-august-1829-first-entry/

[ii] Missouri Historical Society Archives, Digital Identifier D03863

[iii] Greenleaf, William Eliot. The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom. Connecticut: Negro Universities Press, 1970.

Louisa’s letter to her husband Archer Alexander

Leave a reply to Susan Cancel reply